Is It Possible To Change The Shape Of Your Muscles?

By performing certain exercises or by varying the angle at which you train certain muscle, Is it possible to change the shape of your muscles? The purpose of this Blog is to explain one of the most misunderstood subjects in strength training and bodybuilding.

Can we “shape” our muscles with certain exercises?

One of the most misunderstood concepts in bodybuilding is the belief that there are some exercises that shape or define the muscle and others that bulk it up. Unfortunately, the shape or form of a muscle is genetically predetermined and cannot be altered for example, your height or the colour of your eyes. There’s no such a thing as “shaping exercises.” But that doesn’t mean that your physique is predetermined. as Arnold put it in Pumping Iron. You need to look at yourself the way an artist would and decide where do you need more or less “clay”,.

Just to give you an example, we usually consider bench press to be mass building exercise for the chest. On the other hand, cable flyes we usually see as a ‘shaping’ exercise. While performing either exercise, however, the pectorals simply contract and relax. So where does this notion come from?

Most likely, it occurs that heavy benching is done in the off-season, when people are stronger and bigger. During a diet, especially when an athlete is eating fewer carbohydrates and therefore has less energy, many athletes don’t have the strength to perform heavy bench anymore so they resort to cable flyes for a chest workout. Since they are leaner, they conclude that the cable flyes must have done the trick, not the dramatically reduced calories and increased cardio.

So are all exercises created equal?

When training a muscle it is necessary to perform a mid range or power movement and follow that up with a stretch exercise.

As an example, for the chest, one would do incline presses followed by dumbbell flyes with an emphasis on the stretch. The big exercise involves a lot of other muscles such as the triceps and the shoulders and forces the body to release growth hormone during the workout. Following with a stretch motion, the athlete creates tissue tears, which will enable further muscle growth. The body needs to repair those tears, which consumes a lot of energy (fat loss) and makes the muscle stronger (muscle gain) depending on your caloric intake.

The All or Nothing Principle

We can think of a muscle as being similar to a rope. When you tie a rope to a solid object, like a tree, and then pull on it, the rope will be taut through every strand. It is impossible for a part of the rope to be slack while another part is taut; it’s all or nothing.

What about varying the angle at which we train certain muscle?

Our muscles are no different. When we do an exercise that extends the muscle through its range of motion, all of the fibres are activated. That is true even though both ends of the muscle are moving, unlike the tree and rope illustration. We can see this by extending the rope illustration to a tug of war competition.

Regardless of who is winning the competition, the rope will have the same tensions throughout its entire length; there will be no slack strands. This illustrates the all or nothing principle of muscle activation. It is impossible to pull on a rope in such a way that there is more tension on one end and less tension on the other end. Increased or decreased force increases or decreases the force through the entire rope. You cannot isolate a part of it. The bottom line here is that when a muscle is required to contract against a weight, the muscle tension will be evenly distributed across all of the muscle fibres, all the way from the origin point to the insertion.

Are There Inner and Outer Pecs?

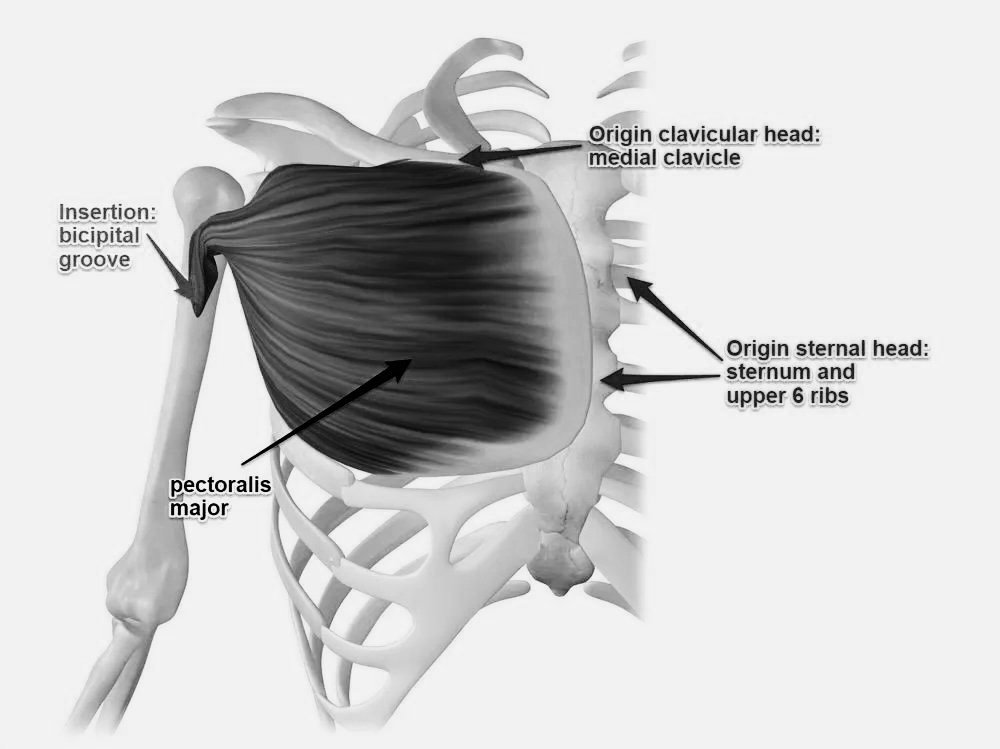

The pectoral muscle fibres run from the centre of the chest (arises from the anterior surface of the sternal half of the clavicle from breadth of the half of the anterior surface of the sternum, as low down as the attachment of the cartilage of the sixth or seventh rib; from the cartilages of all the true ribs, with the exception, frequently, of the first or seventh, and from the aponeurosis of the abdominal external oblique muscle) to the top of the humerus, (a flat tendon, about 5 cm in breadth, which is inserted into the lateral lip of the bicipital groove (intertubercular sulcus) of the humerus. The humerus bone pulls those fibres toward the sternum just the same way that you would pull on a rope, so that every fibre achieves the same level of tautness.

Pectoralis major origin and insertion

Many people believe that when you do a dumbbell press you are working the ‘inner’ part of the pecs, while a dumbbell fly will work the outer portion of the muscle. The difference between the two exercises is the degree to which the elbow is bent, Yet, regardless of whether the elbow is bent more or bent less, the humerus will still pull the pec muscle toward the sternum in exactly the same way. The muscle doesn’t know what position the elbow is in; all it knows is how heavy the load is that it has to move.

The difference between the two exercises is that the length of the operating levers (the upper arm, which is the primary level, and the lower arm, which the secondary lever), changes, That is why you cannot use as much weight on the fly movement. However, the pec fibers are contracting the same way in both exercises. That is because you cannot isolate the inner or outer pecs, no matter what exercise you do. There is some evidence, however, that the stretch that you can achieve with flys can have a fascia stretching effect, increasing muscle growth potential.

There’s also a popular though erroneous belief that by varying the angle at which a muscle is trained, the athlete will somehow be able to direct the stress imposed to specific areas of a muscle and can thereby “shape” the muscle being trained.

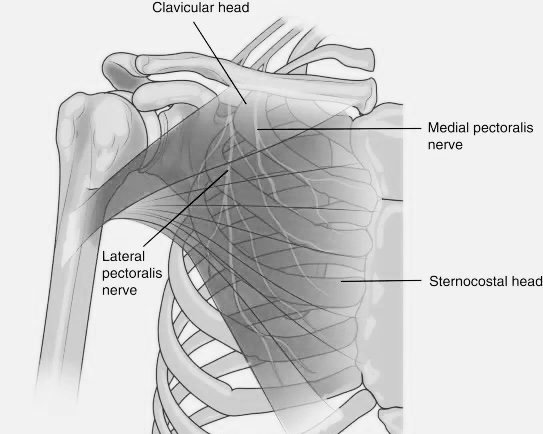

This belief has absolutely no basis in fact. The reason is the way a muscle is innervated. The nerves that enter a given muscle divide out into threads that resemble branches on a tree. Each branch ends at the muscle cell and carries the electrochemical current that causes each muscle cell to contract. When this current is released, all of the cells serviced by the branch (a single neuron) contract simultaneously (the all-or-none law of muscle fibre contraction), not some to the exclusion of others. It’s simply not possible to isolate one portion, border, or ridge of a muscle.

Nerve Innovation of the pectoralis major

Muscle shape is a function of genetics. That’s why the “muscle shaping” advocates can’t perform an exercise to make a biceps muscle look like a triangle or a hexagon.

Genetics

Your genes determine many important pieces of the muscle building puzzle. The shape of your muscles (their length, structure, and where they attach) is just one piece in the puzzle. There is no way you can alter the shape of your muscles by performing certain exercises. There is no such a thing as bulking and shaping exercise. Also, you simply can’t change the shape of a muscle by varying the angle at which you train that concrete muscle.

So don’t waste your precious time trying to shape a muscle into something it cannot become. Al you can do is to make your muscle larger (through progressive intensity), smaller (through lack of use), or stay the same (through no change in intensity). In other words, your muscles can grow bigger in size and they can shrink, but they cannot magically lengthen or become rounded. Of course, stretching can change the tightness of muscles, but that does not change the shape.

Therefore, whether you do Pilates, yoga, or weight training to strengthen and build your muscles, their shape will come out the same. The key difference is that weight training will grow your muscles the fastest. Yoga and Pilates, on the other hand, can offer things that weight training doesn’t, such as extreme flexibility, intense sweating (hot yoga, for instance), and built-in meditation.